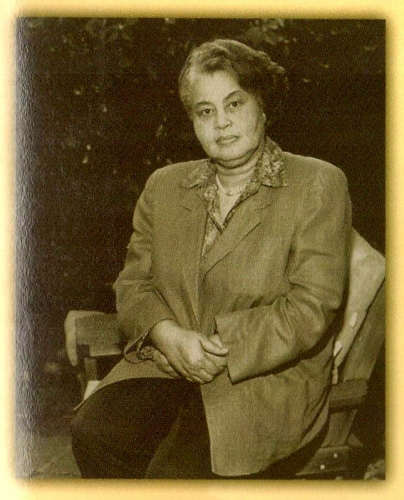

| I never asked Tolstoy to write for me, a little colored girl in Lorain, Ohio. I never asked [James] Joyce not to mention Catholicism or the world of Dublin. Never. And I don’t know why I should be asked to explain your life to you. We have splendid writers to do that, but I am not one of them. It is that business of being universal, a word hopelessly stripped of meaning for me. Faulkner wrote what I suppose could be called regional literature and had it published all over the world. That’s what I wish to do. If I tried to write a universal novel, it would be water. Behind this question is the suggestion that to write for black people is somehow to diminish the writing. From my perspective there are only black people. When I say ‘people,’ that’s what I mean.

~Toni Morrison |

If I had to define what AfroDigital texts look like and do, I would re-mix Morrison’s arguments above and include issues of digital composing and design. I am drawn to her singular goal of offering an unapologetic, self/community-determined right to think, imagine, and create with and for black communities. An AfroDigital pedagogy would seem closely related.

I’ll start here by wondering/wandering about the intellectual, textual community that digital texts can provide. I mean something beyond (for now, at least) the seemingly endless experimentations in classrooms with new technologies as if the experimentation itself is the pursuit of knowledge, a rigorous theory of new media, or the creation of socially critical or meaningful action. I have seen enough youtube videos online made by young people, often for their classes, that deploy quite ingenuous uses of technology but say nothing critical about black communities, fail to transcend the tradition of book reporting, or, at worst, showcase dazzling multimedia tools about nothing. I love when these kind of tech-creative projects are done by 11 and 12 year old students but when the creators are college students, I have some questions, to say the least.

So I am not talking about digital products as the sole marker of an AfroDigital pedagogy.

I am also not talking about the replacement of books and articles since nothing of the sort would be true of my own life. The reading that I do on blogs and other websites does not replace the reading that I do in books and articles, some of it online/e-Book and some not. Nevertheless, I still believe that it is simply no longer enough for a group of students to connect with one another in classroom dialogues or via online discussions alone. Nor is it enough to simply read a book outside of the digital universe that can give vision and audio-dimension to the text. We need to contextualize the world of ideas as part of the digital life that many students already have. For an AfroDigital pedagogy, I am talking about the creation of a fierce, eBlack mini-archive that complements each of our classes.

While students certainly have access to more information and knowledge about black communities and their histories than ever before, I see no evidence of a greater understanding of power, race, and culture today than 20 years ago when I first began teaching when there was no such thing as google, iTunes, or widespread use of DVDs. I don’t expect this understanding from young people since this is the reason, after all, that they are in my classes. However, to talk about the unlimited exchange of knowledge that can be found online severely miseducates students. A google search, for instance, is as coded by money, power, and access in relation to whom and what gets listed, not unlike previous power dynamics that determined whose books/nations made it into a library or printing press.

When I want to link course content to various websites and videos, I clearly need to know that content first in order to sift through the options. For instance, I wanted to build connections for my university program to current scholars’ counter-standardization and counter-testing movements in New York by locating politically challenging video-presentations. I had to know first to look for Pedro Noguera and Michelle Fine because what I got before including their names in my search was inane, at best, and racist, at worst. What about our students who do not know Fine and Noguera as critical, radical thinkers and educational activists? Do we assume they will find these sites and people on their own because the internet is so amazing in the way it equalizes information-gathering from multiple perspectives? Do we assume the internet is so highly interactive and engaging to young people that students will automatically do the work of sifting to find radical nooks and corners? Do we assume they will know, in the example above, to follow the NYCLU on twitter to see the latest activist work they are doing in and for schools? And if they are following NYCLU on twitter, is that the beginning and end, the creme de la creme, of their intellectual work? I say no on all this.

Do we just include a link on a syllabus (or classroom text) or pull up a video in class where oftentimes, like in the case of the panel which hosted Noguera and Fine, contending for our attention, are comments from racist whites about how and why they refuse to send their white children to schools with the poor and dumb black kids in the district? After all, isn’t this what digital spaces allow— free exchange of ideas we may not get otherwise? I say no on all that too.

I can’t afford to assume that our digital universe readily provides access to students to fully humanized representations of black communities. I can’t assume that the most race-critical perspectives have been digitized and easily located for them. I can’t ever assume that students’ possession of a new technological toolkit means that students have a radical or culturally-relevant use of it. So as I plan my class this fall, I am mindful about one, important use of my own website: to gather up and (re)present digital texts as a mini, eBlack archive so that my students and I can focus, think, be, do, and listen better to the black communities we are learning about.

I can’t afford to assume that our digital universe readily provides access to students to fully humanized representations of black communities. I can’t assume that the most race-critical perspectives have been digitized and easily located for them. I can’t ever assume that students’ possession of a new technological toolkit means that students have a radical or culturally-relevant use of it. So as I plan my class this fall, I am mindful about one, important use of my own website: to gather up and (re)present digital texts as a mini, eBlack archive so that my students and I can focus, think, be, do, and listen better to the black communities we are learning about.

When I first began using the term, AfroDigitized, in 2005, I had not heard the 2001 “The Shrine” album compiling a variety of artists from Africa forging what they call futuristic and future sounds of the Motherland. After now hearing that album, I like the term even more as well as this notion of looking and listening digitally to the future, as if it were already here, rather than assuming that we have now is enough. These realizations, at least for me, are small but necessary first steps toward an AfroDigital Pedagogy.

My 20-year old self understood Professor Wynter’s decline of an award as highly principled, but I did not fully understand the conscious and deliberate decision to forego the prestige-conferral ceremonies of Western education. Even though these ceremonies are often divorced from liberatory politics and instead only offer social capital and power, those ceremonies are very enticing for the ways they offer popularity, status, attention, monetary advancement, and upward mobility. This is not to say that we decline all awards, that is not what Professor Wynter did, only that she always rejected any decision that would mark her as part of what

My 20-year old self understood Professor Wynter’s decline of an award as highly principled, but I did not fully understand the conscious and deliberate decision to forego the prestige-conferral ceremonies of Western education. Even though these ceremonies are often divorced from liberatory politics and instead only offer social capital and power, those ceremonies are very enticing for the ways they offer popularity, status, attention, monetary advancement, and upward mobility. This is not to say that we decline all awards, that is not what Professor Wynter did, only that she always rejected any decision that would mark her as part of what  Wynter is, of course, exploding the role of black women in traditional constructions of feminist theory and its applicability outside of whiteness. I now also see the ramification of her embrace of “demonic grounds” in terms of what it means to be a scholar who questions the ways that knowledge and power are maintained in the academy without getting caught up in it and, ultimately, lost in the academic sauce.

Wynter is, of course, exploding the role of black women in traditional constructions of feminist theory and its applicability outside of whiteness. I now also see the ramification of her embrace of “demonic grounds” in terms of what it means to be a scholar who questions the ways that knowledge and power are maintained in the academy without getting caught up in it and, ultimately, lost in the academic sauce.