Oreo. Sell-out. House Negro. Uncle Tom. Aunt Jemima. Incognegro. Miscellaneous. Negro Bed-Wench. Tragic Buck. Coon. Actin White. Talkin White. If a black person says any of these things about another black person, it ain’t a compliment; it is intended as a deep critique of one’s racial mental health and identity. Now, granted, these terms can be used in some of the most problematic and simplistic ways, I admit. Nonetheless, I am drawn to this kind of everyday linguistic system of accountability and obligation that many black folk use to denigrate anything and anyone perceived as an insult and injury to black people. I have grown up with these terms and, quite honestly, have used them to describe many a folk. For me, this language can mark insiders, outsiders, and racial violence in some important ways.

As strange as it might seem, I think it is this very same language that makes me perplexed about many white feminists at times. When the white men who I work with squash all moral obligation and dialogue in the academy, I have seen far too many self-proclaimed “radical” white feminists in these professional settings act in complete alliance with these most bigoted of white male patriarchs and racist systems. And now, when a white female judge and an almost all-white female jury expects us to understand how and why they sympathized with George Zimmerman/white supremacy and sanctioned white terror under the name of the law, I need a radical feminist agenda that will call out such roles under white womanhood (rather than simply ask folk to remember that black women are as demonized as black men). When a white woman goes on national television, accepts a major book contract (she has since cancelled) to explain her situation as one of the jurors in the case, and cries with the expectation that her pain will be a central organizing system for national sympathy in the murder of a black woman’s child, white womanhood has got to be called out as a fundamental mechanism for maintaining white supremacy: white male patriarchy never acts alone. This kind of calling-out is simply an assumption that I readily make from the kind of everyday linguistic system of accountability and obligation that black language has given me. What black folk/black language seems to get as part of its daily consciousness is that we need some words, tropes, images— some language— for this kinda foul, racist stuff.

At the Feminist Wire today, Zillah Eisenstein writes that “Racism in its gendered forms remains the problem here, not simply the law. Racialized gender in the form of the dangerous black boy/man is a form of white privileged terrorism.” Also at the Feminist Wire, Monica Casper makes another compelling case: that we need to talk about “specifically the historical, systemic racism of white women.” And Heather Laine Talley makes it clear that expressions like “well, not all white women/white feminists are like that” is a form of white denial and bad allying. I stand with Eisenstein, Casper, and Talley here. Their posts at the Feminist Wire, on the heels of a series of writings dedicated to Assata Shakur, have been compelling. Meanwhile, Janelle Hobson at Ms. Magazine hits it right on the mark:

Adrienne Rich said it best in “Disloyal to Civilization” when she argued that white women could not form important connections with other women across the planet—the kinds of connections that would advance women’s collective power and overturn patriarchy—if they remained forever loyal to a white supremacist system. This year we’ve seen women like Abigail Fisher try and overturn affirmative action in a Supreme Court case, much like Barbara Grutter before her, even though white women as a group have benefited more than anyone else from affirmative-action programs. And now, another group of women have failed to give Trayvon Martin justice. These instances suggest that white privilege, power and dominance outweigh any notions of gender justice and solidarity.

The white female judge and jury in this case did not experience their own motherhood in sisterhood to the mother of Trayvon Martin, Sybrina Fulton; their motherhood set its gaze only on Zimmerman and property. And the white female judge and jury in this case did not experience the words of a young black woman, Rachel Jeantel, as representative of Knowledge and Truth either. Hobson’s claim that there is no cross-racial gender solidarity in the context of white dominance seems worth heeding.

I am NOT talking here to people who support Zimmerman and the verdict. I know that I am not part of that “sanctified universe of obligation” and have no expectation that dialogue will be possible— American lynch law has never required that the ones swinging from trees be heard and recognized. That ain’t who I think of as my audience, nor where I mark the possibility of a radical humanity and a radical feminism. White femininity in this moment is being (re)scripted in the most dangerous ways and shows itself as, once again, integral to the “sanctified universe of obligation” where white women and families mark themselves as needing protection from black people, especially young black men. This is why I gravitate towards Sylvia Wynter’s re-mix of Helen Fein’s work: you need to look to the decades and centuries preceding a group’s annihilation to see and understand how the dominant group has perpetrated a regime that marks some groups as “pariahs outside the sanctified social order.” It’s a conceptualization that protects us from the claims that we are simplifying history by saying racism today is the same as years before. No, today is not like the lynching of Rubin Stacy as so brilliantly described by Justin Hill at the Black Youth Project. Stacy left Georgia to go to Florida where was murdered on July 19, 1935 in Fort Lauderdale for allegedly trying to harm a white woman (who later reported that he only came to her door begging for food). Apparently, Stacy had walked too closely and too comfortably up to white homes and needed to be killed for it. In the foreground of this now famous lynching photo, you can even see a young white girl, smiling, camera-ready for her special Kodak moment. No, we can’t say that Sanford, Florida is the “exact same” as 1935 Fort Lauderdale, Florida but we CAN say that the “universe of sanctified obligation” created and sustained the murder of Trayvon and the acquittal of his murderer by a white female judge and jury today whose political lenses have, at least partly, manifested from the gaze of that smiling, little girl.

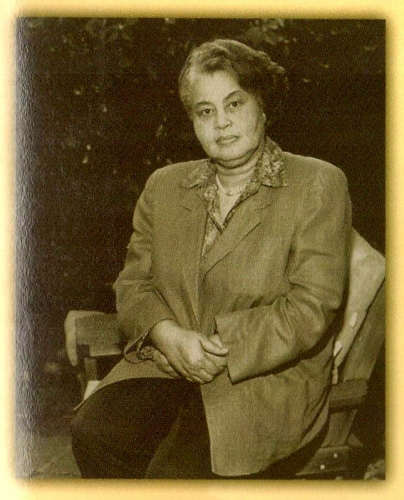

I also go back here to Wynter’s essay, “Beyond Miranda’s Meanings,” where she takes Shakespeare’s play, The Tempest, and shows how Miranda, as a white woman/the only woman in the New World/Island is a “mode of physiognomic being” that gets canonized as the only “rational object of desire” and, therefore, the “genitrix of a superior mode of human life.” What Wynter calls the “situational frame of reference of both Western-European and Euroamerican women writers” has seldom countered this “regime of truth” that must be implicated in the ongoing murder of Trayvon Martin in the courts of the United States. As always, Wynter argues that contending with our present social reality requires a re-writing of the entire episteme and it should be obvious that race AND gender can never be disentangled from this work.

My 20-year old self understood Professor Wynter’s decline of an award as highly principled, but I did not fully understand the conscious and deliberate decision to forego the prestige-conferral ceremonies of Western education. Even though these ceremonies are often divorced from liberatory politics and instead only offer social capital and power, those ceremonies are very enticing for the ways they offer popularity, status, attention, monetary advancement, and upward mobility. This is not to say that we decline all awards, that is not what Professor Wynter did, only that she always rejected any decision that would mark her as part of what

My 20-year old self understood Professor Wynter’s decline of an award as highly principled, but I did not fully understand the conscious and deliberate decision to forego the prestige-conferral ceremonies of Western education. Even though these ceremonies are often divorced from liberatory politics and instead only offer social capital and power, those ceremonies are very enticing for the ways they offer popularity, status, attention, monetary advancement, and upward mobility. This is not to say that we decline all awards, that is not what Professor Wynter did, only that she always rejected any decision that would mark her as part of what  Wynter is, of course, exploding the role of black women in traditional constructions of feminist theory and its applicability outside of whiteness. I now also see the ramification of her embrace of “demonic grounds” in terms of what it means to be a scholar who questions the ways that knowledge and power are maintained in the academy without getting caught up in it and, ultimately, lost in the academic sauce.

Wynter is, of course, exploding the role of black women in traditional constructions of feminist theory and its applicability outside of whiteness. I now also see the ramification of her embrace of “demonic grounds” in terms of what it means to be a scholar who questions the ways that knowledge and power are maintained in the academy without getting caught up in it and, ultimately, lost in the academic sauce.