When I listen to discussions about new technologies and digital pedagogies, I am always struck by how alien that discourse is from the historical and political experiences of African Americans. This is, of course, no surprise given the ways that schools under racial apartheid could hardly foster a culturally or politically relevant education for people of African descent. But the nature and contour of these disconnections are worth examining.

When I listen to discussions about new technologies and digital pedagogies, I am always struck by how alien that discourse is from the historical and political experiences of African Americans. This is, of course, no surprise given the ways that schools under racial apartheid could hardly foster a culturally or politically relevant education for people of African descent. But the nature and contour of these disconnections are worth examining.

I am reminded of conversations that I have heard about people’s general anxiety and discomfort about the public nature of digital texts. I certainly agree with this stance but, at times, quite honestly, the paranoia seems completely unfounded to me. This anxiety comes from an assumption that feels more nested with privilege than with any reality that I can see. The underlying assumption goes something like this: when I show up, everyone will notice. Meanwhile, the amount of time, care, and attention that bloggers and website designers must give to bring regular, continual “traffic” to their site is immense. In terms of a digital universe, you do not simply post online products and have multiple readers and followers right away who then stay with you. What would make people think otherwise? So another assumption operating here is this: as soon as I speak/write, people are listening. I can’t imagine a reality more foreign to women of color. I can’t pinpoint when and where I first learned this lesson but I can be sure that, as a woman of color (unless I am trying to be like or only “theorize” the likes of Basketball Wives, etc), mainstream perspective-bearers are seldom listening and if they are, it is often from the place of hostility, feigned interest, paternalism, or resistance. I don’t know what it is like to assume that when I speak, write, or post online, or anywhere, that I have an immediate and/or large audience. That’s a kind of privilege I simply have not experienced.

Then there is another discourse that I hear a lot, a discourse that I myself have been working diligently to avoid: the issue of control. I often hear this idea that in a digital universe, you can control your public image and presence. Now that’s another hard pill for me to swallow. At what point in history have black folk been able to control their public image? I mean, really! Do we need to be reminded of what happened to Trayvon Martin for Walking while Black, wearing a hoodie and eating skittles? Do we need to be reminded of the endless questioning of President Obama’s citizenship and birth status? A black president can’t even control THAT! This idea that people can control their public presence just reeks of a privileged mindset and history that I can’t understand as anything other than empire. This is not to say that communities of color have no agency, that we are mere victims of an onslaught of visual images that present us as animals. We must, of course, actively construct our images and public presence in a world that is seeking to deny our humanity. There is, after all, a word for that: RHETORIC. The issue of control is a serious one for me because it is a concept so alien to how people of color have needed to imagine and operate in public spaces that it is void of any meaning for us. I think here of a blog that I follow— the Crunk Feminist Collective— who quite forthrightly present themselves as inserting an unapologetic crunk, black, of/color, contemporary feminist discourse into the public sphere. In my mind, that’s a very specific audience and yet, when I read the folk who comment regularly to the collective’s posts, I am often baffled that so many folks outside of that political vision assume the right to try and “correct” what the Crunk Feminists are doing, saying, and theorizing with an often unashamed homophobia, sexism, and/or racism. To their credit, the Crunk Feminists handle them fools something lovely, which all brings me back to my original point: some of us simply can’t control our image and public presence in a capitalistic, racist, heterosexist world. But we DO fight for the right to have that public presence and resistance.

Then there is another discourse that I hear a lot, a discourse that I myself have been working diligently to avoid: the issue of control. I often hear this idea that in a digital universe, you can control your public image and presence. Now that’s another hard pill for me to swallow. At what point in history have black folk been able to control their public image? I mean, really! Do we need to be reminded of what happened to Trayvon Martin for Walking while Black, wearing a hoodie and eating skittles? Do we need to be reminded of the endless questioning of President Obama’s citizenship and birth status? A black president can’t even control THAT! This idea that people can control their public presence just reeks of a privileged mindset and history that I can’t understand as anything other than empire. This is not to say that communities of color have no agency, that we are mere victims of an onslaught of visual images that present us as animals. We must, of course, actively construct our images and public presence in a world that is seeking to deny our humanity. There is, after all, a word for that: RHETORIC. The issue of control is a serious one for me because it is a concept so alien to how people of color have needed to imagine and operate in public spaces that it is void of any meaning for us. I think here of a blog that I follow— the Crunk Feminist Collective— who quite forthrightly present themselves as inserting an unapologetic crunk, black, of/color, contemporary feminist discourse into the public sphere. In my mind, that’s a very specific audience and yet, when I read the folk who comment regularly to the collective’s posts, I am often baffled that so many folks outside of that political vision assume the right to try and “correct” what the Crunk Feminists are doing, saying, and theorizing with an often unashamed homophobia, sexism, and/or racism. To their credit, the Crunk Feminists handle them fools something lovely, which all brings me back to my original point: some of us simply can’t control our image and public presence in a capitalistic, racist, heterosexist world. But we DO fight for the right to have that public presence and resistance.

I will call my last point of disconnection the Sleeping Beauty complex. As an educator, I see a wide continuum of how people relate to technology: on one far end are the people who fetishize any and every new thing; way on the other end are the folk who demonize anything related to technology (often while maintaining a Facebook account, of course); in between is a whole range of perspectives and experiences. The folk who baffle me most though are those sitting and waiting for the institution to tell them exactly what to do and to train them exactly how to do it. The kind of trust you must have in institutions to sit, wait, and expect all that is just not something I can relate to. That kind of passivity and faith means that you don’t really understand or critique institutions as spaces in place and time that invent and sustain power, presumably because you share that power. Or, similarly, you want a piece of that power and are waiting for the opportunity to cash in. For me, this kind of Sleeping Beauty complex where I wait for the king to arrive means giving up all self-determination: the desire to willingly forego my own decision-making and meaning-making by simply waiting for the institution/empire to tell me what to do, in other words, to bestow its imprint on me. That kind of waiting only works for those who already expect and represent power, which simply has not been the historical experience of black communities.

I will call my last point of disconnection the Sleeping Beauty complex. As an educator, I see a wide continuum of how people relate to technology: on one far end are the people who fetishize any and every new thing; way on the other end are the folk who demonize anything related to technology (often while maintaining a Facebook account, of course); in between is a whole range of perspectives and experiences. The folk who baffle me most though are those sitting and waiting for the institution to tell them exactly what to do and to train them exactly how to do it. The kind of trust you must have in institutions to sit, wait, and expect all that is just not something I can relate to. That kind of passivity and faith means that you don’t really understand or critique institutions as spaces in place and time that invent and sustain power, presumably because you share that power. Or, similarly, you want a piece of that power and are waiting for the opportunity to cash in. For me, this kind of Sleeping Beauty complex where I wait for the king to arrive means giving up all self-determination: the desire to willingly forego my own decision-making and meaning-making by simply waiting for the institution/empire to tell me what to do, in other words, to bestow its imprint on me. That kind of waiting only works for those who already expect and represent power, which simply has not been the historical experience of black communities.

While these expectations related to audience, control of public presence, and the benevolent caretaking of institutions seem so simple and “everyday”, they are deeply invested in social hierarchies. Since I do not sit at the top of these hierarchies, the view down here gives me a different perspective on how and why these everyday topics circulate. These are perspectives that digitally-emboldened, color-conscious students also need to hear and think about.

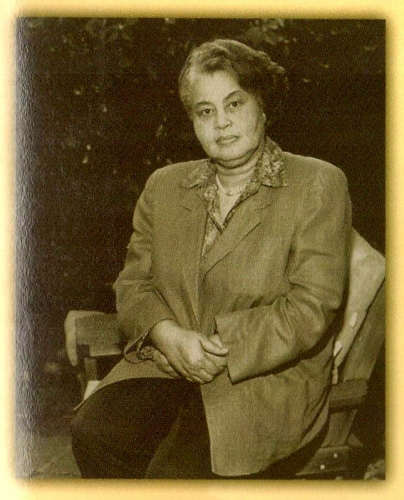

My 20-year old self understood Professor Wynter’s decline of an award as highly principled, but I did not fully understand the conscious and deliberate decision to forego the prestige-conferral ceremonies of Western education. Even though these ceremonies are often divorced from liberatory politics and instead only offer social capital and power, those ceremonies are very enticing for the ways they offer popularity, status, attention, monetary advancement, and upward mobility. This is not to say that we decline all awards, that is not what Professor Wynter did, only that she always rejected any decision that would mark her as part of what

My 20-year old self understood Professor Wynter’s decline of an award as highly principled, but I did not fully understand the conscious and deliberate decision to forego the prestige-conferral ceremonies of Western education. Even though these ceremonies are often divorced from liberatory politics and instead only offer social capital and power, those ceremonies are very enticing for the ways they offer popularity, status, attention, monetary advancement, and upward mobility. This is not to say that we decline all awards, that is not what Professor Wynter did, only that she always rejected any decision that would mark her as part of what  Wynter is, of course, exploding the role of black women in traditional constructions of feminist theory and its applicability outside of whiteness. I now also see the ramification of her embrace of “demonic grounds” in terms of what it means to be a scholar who questions the ways that knowledge and power are maintained in the academy without getting caught up in it and, ultimately, lost in the academic sauce.

Wynter is, of course, exploding the role of black women in traditional constructions of feminist theory and its applicability outside of whiteness. I now also see the ramification of her embrace of “demonic grounds” in terms of what it means to be a scholar who questions the ways that knowledge and power are maintained in the academy without getting caught up in it and, ultimately, lost in the academic sauce.