I attended a conference this summer and though many of the researchers and presenters left a lasting and positive impression, there was one graduate student who I still just can’t get out of my head. I don’t know her name but I found her absolutely entertaining to observe, albeit somewhat horrifying.

I was standing outside of a room, waiting for that session to end, when I overheard this woman talking with other graduate students who she had obviously met at the conference. She explained a very specific conference strategy: she attended the sessions of the most famous scholars, made sure to sit up in front, ask really smart questions publicly in the session, and then go talk to the individual presenters after the session. This, according to her, was how you get the “famous people” to notice you, remember you, work with you, and help you forward your career. I found this conversation absolutely fascinating so I did the inevitable: I watched her… because when someone doesn’t see you, you’d be surprised at just how much you can see of them. She did not disappoint. In every feature session, there she was: all up in the front, asking a question with little regard for whether or not it actually contributed something to the conversation, and then there she was on the que waiting to talk to folk afterwards. I was wildly entertained, I will admit, but I am, at the same time, sympathetic to her cause. She was only mirroring the kind of superficiality that academic culture sustains today, a culture that is telling a young black woman grabbing at a Ph.D. that groupie-stalking is what it takes for her to survive and thrive in the academy, not a serious engagement with ideas and thinking. While this young woman’s practice might seem, well, a bit CRAZY, what was more astonishing was the actual response from the “famous people.” They ate it up like famished souls where only this kind of attention could satiate their hunger.

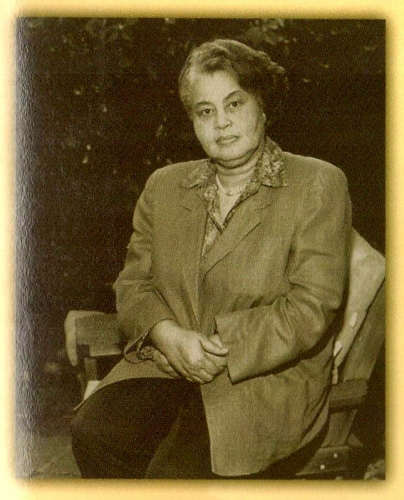

These are the moments when I often think of Professor Wynter, when I am reminded that the work one does is the WORK one does: the way you live out your life is the way that you live out your words on the page too. They are not opposing forces. What concerns me most about the young woman who I have described is that the reality she describes for being noticed was not a hallucination on her part. It served her to good effect at the conference and it might also serve her to good effect in her larger career.

Meanwhile, every chance Wynter gets, she reminds her audiences to think past the epistemic boundaries of a given world/social order and reach out past it, as evidenced even in a letter she wrote to the Centre for Caribbean Thought. Even in only a letter, she talks about what it means to be “world-historical people” who have no choice but confront “the imperative of the effecting of a profound mutation in what is now the globally hegemonic Western European, secular, and thereby naturalized understanding of being human.” It becomes wildly absurd then to imagine trying to get the attention of famous people at an academic conference in the context of Wynter’s call that we begin to completely upturn the “naturalized, now biologized, globally homogenized, homo oeconomicus understanding of being human” so that we can finally displace its referential system with its “now internet-integrated planet of the middle class suburbia/exurbia/gentrified inner city ‘referent we, on the one hand, and on the other, that of the rapidly urbanizing ‘planet of slums.’ ”

It makes sense to me that Wynter does not call the “Crisis of the Negro Intellectual” in this historical moment ONLY the product of white liberalism and racism in the academy. She loads that crisis with the processes and products of what black scholars themselves have created in the quest to replicate the very models which had ontologically, intellectually, and aesthetically excluded them in the first place, fully incorporating all of its cognitive closures and impediments to radical social change. That’s more than a notion right there! I also see Wynter’s points here in the very way that she enacts her scholarly identity. I am often amazed at how connected I feel to other scholars who deeply engage her work, a connection I had never once even articulated to myself because it just seems so self-evident. But even this aspect of her scholarly identity points to the alternate space in which she does intellectual work. I am often stunned by how graduate students, for instance, of a specific scholar will go above and beyond to “market” themselves as the heir of that advisor (i.e., which can quickly become the “auction block” code for which plantation provided the best skills) and/or do their best to patrol who and how their advisor is referenced (making the example of the woman I describe all the more believable). Scholarship in this mode becomes a kind of white property to be maintained and sustained by measuring its exchange value against other properties. I no longer think it is a mere coincidence that the folk I know who engage Wynter do not unleash these kind of beasts/pseudo-intellectual pathologies. In fact, it seems safe to say that Wynter herself would not allow it!

I certainly don’t mean to harshly castigate the young woman who I described at the beginning of this post. Like I said, I am sympathetic and very concerned for her cause. At this point in my life and career, I find myself most drawn and interested in those black thinkers and scholars who are really interested in liberation rather than bling, status, and attention. I think this is why I have become so much more deeply grateful for the model that Sylvia Wynter offers, a model that has lately become a kind of life preserve in this sea I must swim in.

My 20-year old self understood Professor Wynter’s decline of an award as highly principled, but I did not fully understand the conscious and deliberate decision to forego the prestige-conferral ceremonies of Western education. Even though these ceremonies are often divorced from liberatory politics and instead only offer social capital and power, those ceremonies are very enticing for the ways they offer popularity, status, attention, monetary advancement, and upward mobility. This is not to say that we decline all awards, that is not what Professor Wynter did, only that she always rejected any decision that would mark her as part of what

My 20-year old self understood Professor Wynter’s decline of an award as highly principled, but I did not fully understand the conscious and deliberate decision to forego the prestige-conferral ceremonies of Western education. Even though these ceremonies are often divorced from liberatory politics and instead only offer social capital and power, those ceremonies are very enticing for the ways they offer popularity, status, attention, monetary advancement, and upward mobility. This is not to say that we decline all awards, that is not what Professor Wynter did, only that she always rejected any decision that would mark her as part of what  Wynter is, of course, exploding the role of black women in traditional constructions of feminist theory and its applicability outside of whiteness. I now also see the ramification of her embrace of “demonic grounds” in terms of what it means to be a scholar who questions the ways that knowledge and power are maintained in the academy without getting caught up in it and, ultimately, lost in the academic sauce.

Wynter is, of course, exploding the role of black women in traditional constructions of feminist theory and its applicability outside of whiteness. I now also see the ramification of her embrace of “demonic grounds” in terms of what it means to be a scholar who questions the ways that knowledge and power are maintained in the academy without getting caught up in it and, ultimately, lost in the academic sauce.