I have fond, childhood memories of this time: the kitchen of the aunt who helped raise me and the joy and laughter everywhere when we were stuck inside in the Ohio, winter months. I have memories of my cousins, the single mothers, who always talked to me like an adult even when I was really young, explaining how they planned and saved money for their children’s gifts beginning in July and August. They were all struggling in all kinds of ways but always saw to it that their children would smile every Christmas morning (it was only as an adult that I figured out that my mother was doing the same.) It wasn’t about the gifts ever, just surrounding their children with the kind of wonder and awe that poor people are not supposed to experience. The financial planning that working class/working poor single mothers did back then during the holidays (no one I knew had credit cards) represents a financial genius that could re-organize our collapsing economic system, if that was what we really wanted! A working class, single mother who is doing it all on her own, without the social imprint of needing male (sexual) attention or patriarchal protection, has a formidable skills-set, at this time of the year and every other time. So every year around now, I especially remember these women. I certainly see and appreciate all of the listings of suggested eco/cultural/conscious gifts to buy during the holidays, but I also remember an anti-capitalist analysis of the greatest ploy in the Western world to keep today’s working class in debt. It was young, working class black single mothers— my very own cousins who made me into the little sister who would carry their heart’s torch— who gave me this political lens.

I have fond, childhood memories of this time: the kitchen of the aunt who helped raise me and the joy and laughter everywhere when we were stuck inside in the Ohio, winter months. I have memories of my cousins, the single mothers, who always talked to me like an adult even when I was really young, explaining how they planned and saved money for their children’s gifts beginning in July and August. They were all struggling in all kinds of ways but always saw to it that their children would smile every Christmas morning (it was only as an adult that I figured out that my mother was doing the same.) It wasn’t about the gifts ever, just surrounding their children with the kind of wonder and awe that poor people are not supposed to experience. The financial planning that working class/working poor single mothers did back then during the holidays (no one I knew had credit cards) represents a financial genius that could re-organize our collapsing economic system, if that was what we really wanted! A working class, single mother who is doing it all on her own, without the social imprint of needing male (sexual) attention or patriarchal protection, has a formidable skills-set, at this time of the year and every other time. So every year around now, I especially remember these women. I certainly see and appreciate all of the listings of suggested eco/cultural/conscious gifts to buy during the holidays, but I also remember an anti-capitalist analysis of the greatest ploy in the Western world to keep today’s working class in debt. It was young, working class black single mothers— my very own cousins who made me into the little sister who would carry their heart’s torch— who gave me this political lens.

At this time of year, I also turn my gaze to the Winter Solstice, thanks to the help of a college friend a few years back who has shared some of the most significant spiritual insights with me. Now, let me be clear. I am no Solstice Purist, Expert, or ardent Practitioner. There have been times when I try to get out of Solstice work by seeking an astrological reading. The results usually tell me that I’m stubborn, stank, and sometimes rather unyielding, things I already know. I don’t get much from this information other than, perhaps, a justification for why I have a tendency to yell at folk in the NYC subway: “get…YO… a$%… out… the… way!” (I mean, really, you canNOT stop and answer a text message on a subway stairway when 50 people are coming full force behind you!) I have, thus, figured that I can’t really replace the opportunities that the Winter Solstice provides with an “astrological reading.”

The Winter Solstice takes place this year for four days and four nights, December 21 to December 24 (according to nautical calendars), the time when the sun is at its southernmost position. This is that time when the sun rises at the latest in the day and sets at the earliest of the entire year. The day is shortest; the night is longest. For the Ancients in Kemet, enlightenment is literally written into the cosmos, in this very movement of the sun and stars. Light gradually increases in the winter sunrise, hence, offering a kind of spiritual rebirth. This means that you can use the time of the Winter Solstice to discover your purpose and realize true spiritual power, but only if you slow down and tap into it.

My ideas are shaped mostly from Ra Un Nefer Amen who makes a plea for intensive meditation during the Winter Solstice when the gates between the spiritual realm and the lived world are open (by spiritual realm, he means spirit, subconscious, or even what Jung called unconscious.) Though I am not following his prescriptive formula for meditation at the Solstice, Ra Un Nefer Amen’s teachings seem invaluable, namely that we often live out a toxic program that we intentionally create for ourselves. We are not passive onlookers of our own lives and instead invent and design our own programs of stunning self-destruction with the choices we make: how we spend our money, who we choose to have intimate relationships with, how we treat our bodies/our health, and how we approach or stall our work/career. Since spirit carries out the behavior that manifests these negative things in our lives, then spirit is what we need to work on. What makes ancient cultures important here (Amen’s focus is on Kemet) is that they believe the Winter Solstice was the time that the spirit could receive a new message and, therefore, discard old, toxic programming. Getting rid of a toxic program is not an easy thing, a feat few people ever really achieve (and spend a lot of money on therapy for), hence, the importance and weight of the intervention of the Winter Solstice. These are all, of course, very simplistic lenses into what Kemetic philosophers like Amen believe and say, but you see where I am going here.

My ideas are shaped mostly from Ra Un Nefer Amen who makes a plea for intensive meditation during the Winter Solstice when the gates between the spiritual realm and the lived world are open (by spiritual realm, he means spirit, subconscious, or even what Jung called unconscious.) Though I am not following his prescriptive formula for meditation at the Solstice, Ra Un Nefer Amen’s teachings seem invaluable, namely that we often live out a toxic program that we intentionally create for ourselves. We are not passive onlookers of our own lives and instead invent and design our own programs of stunning self-destruction with the choices we make: how we spend our money, who we choose to have intimate relationships with, how we treat our bodies/our health, and how we approach or stall our work/career. Since spirit carries out the behavior that manifests these negative things in our lives, then spirit is what we need to work on. What makes ancient cultures important here (Amen’s focus is on Kemet) is that they believe the Winter Solstice was the time that the spirit could receive a new message and, therefore, discard old, toxic programming. Getting rid of a toxic program is not an easy thing, a feat few people ever really achieve (and spend a lot of money on therapy for), hence, the importance and weight of the intervention of the Winter Solstice. These are all, of course, very simplistic lenses into what Kemetic philosophers like Amen believe and say, but you see where I am going here.

My ruminations here on the Winter Solstice might seem strange or even offensive to friends who are, on one side, atheist or agnostic, and, on the other side, deeply committed to their specific church or religious doctrines. I myself have not been fully acculturated into these belief systems and do not go any deeper than what I have said here. I intend no disrespect to anybody, only the suggestion that the ways the Ancients saw these coming days, the axes of the sun, the value of deep meditation, and the general process where you slowwww down can’t be all that bad. I can’t see a more pressing need for exactly such a practice when all anyone seems to be doing now is spending money, accruing debt and interest on charge cards, running around frantically, or being angry at hyper-consumerism. This seems like the best time for me to be tapping into who I am and all that I can still become. Though I couldn’t articulate it back then, I now see the working class/working poor single mothers who cocooned my girlhood as women who must have been able to tap into a powerful site where their spirit resided. Yes, they used their youth, radical black female subjectivity and working class consciousness to read their political environments brilliantly, but they also lived their lives from a powerful center/spirit. There is just no other way that you can move the kinds of mountains they did without that. As I finish my last days grading and work towards the challenge of reconnecting with my own spirit, I’ll be thinking of them.

My ruminations here on the Winter Solstice might seem strange or even offensive to friends who are, on one side, atheist or agnostic, and, on the other side, deeply committed to their specific church or religious doctrines. I myself have not been fully acculturated into these belief systems and do not go any deeper than what I have said here. I intend no disrespect to anybody, only the suggestion that the ways the Ancients saw these coming days, the axes of the sun, the value of deep meditation, and the general process where you slowwww down can’t be all that bad. I can’t see a more pressing need for exactly such a practice when all anyone seems to be doing now is spending money, accruing debt and interest on charge cards, running around frantically, or being angry at hyper-consumerism. This seems like the best time for me to be tapping into who I am and all that I can still become. Though I couldn’t articulate it back then, I now see the working class/working poor single mothers who cocooned my girlhood as women who must have been able to tap into a powerful site where their spirit resided. Yes, they used their youth, radical black female subjectivity and working class consciousness to read their political environments brilliantly, but they also lived their lives from a powerful center/spirit. There is just no other way that you can move the kinds of mountains they did without that. As I finish my last days grading and work towards the challenge of reconnecting with my own spirit, I’ll be thinking of them.

“Christmas always came to our house, but Santy Claus only showed up once in a while.” I love this line. It does so much in just 16 words. “Santy Claus” is marked as Other both in how it is named and located as a secondary, um, clause. It literally delivers Christmas from its consumerist saga and resets it within new sets of practices and values. The line comes from none other than the children’s book written by

“Christmas always came to our house, but Santy Claus only showed up once in a while.” I love this line. It does so much in just 16 words. “Santy Claus” is marked as Other both in how it is named and located as a secondary, um, clause. It literally delivers Christmas from its consumerist saga and resets it within new sets of practices and values. The line comes from none other than the children’s book written by  In the story, beautifully illustrated by Jerry Pinkney, three sisters receive one special gift: Baby Betty Doll. The sisters, once inseparable— called chickadees by their mother, because they were always chattering, twittering, and doing everything together— are now fighting amongst one another. When Santy Claus actually does visit in one auspicious year with the beloved Baby Betty Doll, conflict arises since all three must share the one, coveted doll. Nella convinces her two sisters that Baby Betty was her idea and written request to Santy so she should receive the doll. The other two sisters begrudgingly agree and go on to play outside without their sister. Nella thinks she is going to have the best day of her life, only to find out it becomes the worst: playing with the doll, all alone, without her sister’s company, bores her to tears. She apologizes to her two sisters and from there, they work out a plan so that the doll can belong to all three of them. It the end, they learn that all they really want for Christmas is themselves, their creativity, togetherness, and family, not a store-bought item.

In the story, beautifully illustrated by Jerry Pinkney, three sisters receive one special gift: Baby Betty Doll. The sisters, once inseparable— called chickadees by their mother, because they were always chattering, twittering, and doing everything together— are now fighting amongst one another. When Santy Claus actually does visit in one auspicious year with the beloved Baby Betty Doll, conflict arises since all three must share the one, coveted doll. Nella convinces her two sisters that Baby Betty was her idea and written request to Santy so she should receive the doll. The other two sisters begrudgingly agree and go on to play outside without their sister. Nella thinks she is going to have the best day of her life, only to find out it becomes the worst: playing with the doll, all alone, without her sister’s company, bores her to tears. She apologizes to her two sisters and from there, they work out a plan so that the doll can belong to all three of them. It the end, they learn that all they really want for Christmas is themselves, their creativity, togetherness, and family, not a store-bought item. Like she does with Christmas in the Big House, Christmas in the Quarters, McKissack uses historical research to write The All-I’ll-Ever-Want Christmas Doll also. This book is not a world of make believe or simply a story about learning to share. I was surprised to see how many introductions and discussions of the book leave out the one, very important character who McKissack introduces at the very start in her “Note about the Story”: Mary Lee Bendolph. Once again, we see the white liberalist imperative of a false “universalism” wipe away black historical specificity. The All-I’ll-Ever-Want Christmas Doll is the narrative of

Like she does with Christmas in the Big House, Christmas in the Quarters, McKissack uses historical research to write The All-I’ll-Ever-Want Christmas Doll also. This book is not a world of make believe or simply a story about learning to share. I was surprised to see how many introductions and discussions of the book leave out the one, very important character who McKissack introduces at the very start in her “Note about the Story”: Mary Lee Bendolph. Once again, we see the white liberalist imperative of a false “universalism” wipe away black historical specificity. The All-I’ll-Ever-Want Christmas Doll is the narrative of  It was a fellow second grader who first told me that Santa Claus was not real. I remember coming home with many questions, not about Santa, but about everything else I could think of. The tooth fairy, the Easter Bunny, Mickey Mouse, the talking animals in my children’s books, Scooby Doo, Bugs Bunny and EVEN Wonder Woman were not real. That’s a lot for a child to ingest in one day. There was one fiction that I never questioned though. It was a story that a family friend, who I think of as an uncle, told me. I had come home excited from school talking non-stop about what I had learned about President George Washington. My uncle told me to rethink my excitement because the Big G.W. wasn’t all that. According to him, GW chopped down momma’s cherry tree, lied about it, and so my uncle had no choice but to whup dat ass. I told everyone about my amazing uncle after that, despite the naysayers and player-haters who insisted that my uncle was not old enough to know GW. My uncle IS old was my vehement response. Plus, my uncle had animatedly replayed the whole conversation for me. You couldn’t make up something like that as far as I was concerned. I offer this story not to highlight my eventual discovery of my uncle’s age and tall-tale-telling but as a way to counter a problematic Christmas book about African American children. The fact that my uncle, a man who cannot read and write, replaced white greatness with people who look like me in an everyday children’s conversation is a kind of love and political capacity that escapes far too many.

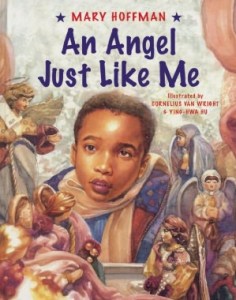

It was a fellow second grader who first told me that Santa Claus was not real. I remember coming home with many questions, not about Santa, but about everything else I could think of. The tooth fairy, the Easter Bunny, Mickey Mouse, the talking animals in my children’s books, Scooby Doo, Bugs Bunny and EVEN Wonder Woman were not real. That’s a lot for a child to ingest in one day. There was one fiction that I never questioned though. It was a story that a family friend, who I think of as an uncle, told me. I had come home excited from school talking non-stop about what I had learned about President George Washington. My uncle told me to rethink my excitement because the Big G.W. wasn’t all that. According to him, GW chopped down momma’s cherry tree, lied about it, and so my uncle had no choice but to whup dat ass. I told everyone about my amazing uncle after that, despite the naysayers and player-haters who insisted that my uncle was not old enough to know GW. My uncle IS old was my vehement response. Plus, my uncle had animatedly replayed the whole conversation for me. You couldn’t make up something like that as far as I was concerned. I offer this story not to highlight my eventual discovery of my uncle’s age and tall-tale-telling but as a way to counter a problematic Christmas book about African American children. The fact that my uncle, a man who cannot read and write, replaced white greatness with people who look like me in an everyday children’s conversation is a kind of love and political capacity that escapes far too many. On Cyber Monday, I searched the corners of google and bing for

On Cyber Monday, I searched the corners of google and bing for  A friend recently suggested that I watch an interview with Marianne Williamson where she talks about love. Now, some of that New Age spirituality gets a little weird to me, but, hey, to each their own. Some of it just borrows too heavily from Non-Western spiritual traditions and remixes all of that for American, bourgeois individualism. Nevertheless, there are times when a definition or phrase moves me deeply. In this interview, Williamson gives a definition of love that describes black folk beautifully. She is not, of course, talking explicitly about black people, but about a kind of everyday practice that I attribute to them: “a spiritual, mental, emotional, personal strength that I develop in myself to refuse to see you as other people might have chosen to see you today.” She calls this a kind of sacred, daily practice when you “give birth, rebirth, to [someone’s] own self-confidence, their own belief in themselves, their own strength and glory, because you see what others might not see.” I get this kind of sacred practice and strength everytime I talk to one of my sistafriends and mentors who refuse to see me from the lens of a violating, white, dominant gaze. I also get this every time I talk to one of my colleagues of color about something that has happened; they don’t ever act like I am overreacting or sweep everything under the rug like most white colleagues do— they have the ability to see and hear me and offer an alternative paradigm outside of white norms. I can’t think of a better definition than SACRED to describe the teachers, mentors, parents, family, extended family, scholars, friends who see the beauty of black children and families, and choose to portray that back, despite the world that constantly suggests otherwise. I can tell you that it is ONE HELLUVA thing to step out in a world each day that tries to minimize my expertise, question my awareness/consciousness/ability… but then come home to a partner, sistafriend, auntie, uncle, pops, momma, or neighbor who tells me to keep on keeping on, moves me past the toxic energy of dumb folk, and reminds me of who and what I am. One Helluva Thing! Though this book ain’t worth the paper it is printed on, its ignorance did remind me to always remember what Black Love is and does.

A friend recently suggested that I watch an interview with Marianne Williamson where she talks about love. Now, some of that New Age spirituality gets a little weird to me, but, hey, to each their own. Some of it just borrows too heavily from Non-Western spiritual traditions and remixes all of that for American, bourgeois individualism. Nevertheless, there are times when a definition or phrase moves me deeply. In this interview, Williamson gives a definition of love that describes black folk beautifully. She is not, of course, talking explicitly about black people, but about a kind of everyday practice that I attribute to them: “a spiritual, mental, emotional, personal strength that I develop in myself to refuse to see you as other people might have chosen to see you today.” She calls this a kind of sacred, daily practice when you “give birth, rebirth, to [someone’s] own self-confidence, their own belief in themselves, their own strength and glory, because you see what others might not see.” I get this kind of sacred practice and strength everytime I talk to one of my sistafriends and mentors who refuse to see me from the lens of a violating, white, dominant gaze. I also get this every time I talk to one of my colleagues of color about something that has happened; they don’t ever act like I am overreacting or sweep everything under the rug like most white colleagues do— they have the ability to see and hear me and offer an alternative paradigm outside of white norms. I can’t think of a better definition than SACRED to describe the teachers, mentors, parents, family, extended family, scholars, friends who see the beauty of black children and families, and choose to portray that back, despite the world that constantly suggests otherwise. I can tell you that it is ONE HELLUVA thing to step out in a world each day that tries to minimize my expertise, question my awareness/consciousness/ability… but then come home to a partner, sistafriend, auntie, uncle, pops, momma, or neighbor who tells me to keep on keeping on, moves me past the toxic energy of dumb folk, and reminds me of who and what I am. One Helluva Thing! Though this book ain’t worth the paper it is printed on, its ignorance did remind me to always remember what Black Love is and does.