There are times when talking to my poet-friends is just so difficult. You’ll say something and it will remind them of a memory or a line they had in their heads, so they will just interrupt the conversation and start writing. You can be in the middle of dinner, talkin about sumthin real intense too, and then, all of a sudden, BAM, they stop cold-turkey and write in their notebooks. I suppose I annoy people too, because I am always delighted by and stop dead in my tracks for African American language patterns. I can get as enthralled by the content as the language and start crackin up at the ways my friends say things, not because it’s funny, per se, but because of their cleverness and verbal dexterity. I can’t help but trace the deep, sociological specificity of how, when, why, and where a term or expression is used. “I ain’t got time fa dat”/“I ain’t got NO time fa dat” is one of my favorite expressions, interchangeable with: “aint nobody got time fa dat” or “aint nobody got time fa you” (a few expletives might also come.) This expression is certainly not new since I have heard elders use it for as long as I can remember, so I suspect that my age and current circumstances correspond to its new frequency in my discursive toolkit.

Sweet Brown from a White Perspective

For many non-Black folk, the first time they noticed this expression was from the now infamous, internet-sensation Sweet Brown in early 2012. When Sweet Brown escaped an apartment fire in Oklahoma City, she told the local news that she left, without shoes or clothes, and ran for her life. After then explaining that she has bronchitis and the smoke was getting to her, she proclaimed: “Ain’t nobody got time for that.” From that point on, the memes and remixes ridiculed her, circulating her last words seemingly endlessly, with of course, an incessant focus on her headscarf. Ironically, with all that arrogance and surety that she was saying something simple, none of these folk were smart enough to actually know what Sweet Brown was articulating: about the apartment building, about her life, about her health, and about her social circumstances as a black woman. The time spent on caricaturing her voice and look was appalling, though she SAID she ran out the house unable to even put on shoes. And, true to white appropriation, not a single meme used the expression correctly. Most of these folk even thought Sweet Brown INVENTED the expression. Unfortunately, not enough black folk saw the light either.

Sweet Brown… Through the Fire!

The use of “that” in “I ain’t got time fa dat” is never solely about a specific event you simply cannot attend or that causes an inconvenience for you. “That” means pure foolishness, the kind of mess you should not have to waste your time, essence, energy, and spirit on. If someone asks me if I am going to a certain event and I say, “naw I ain’t got time fa dat,” I am making a criticism of the event, the people involved, the ideas being promulgated, and the social world being maintained. I am NOT talking about a conflict with my schedule, calendar, or date book! On top of that, I am proclaiming the worth of my energy and attention in relation to the sponsoring person, event, or issue. It is a public declaration aimed at re-assessing the worth of the speaker and the listeners who she is trying to define the world for and with. I see black folk everywhere publicly proclaiming who and what they don’t respect with this obvious phrase and yet so many miss the meaning. I mean, really: you can tell folk to their faces that you ain’t feelin em too tough and they will think you are talking about your dayplanner! In the words of James Baldwin: “If Black English Isn’t a Language, Then Tell Me, What Is!”

Of course, it goes deeper. It also depends on HOW you say it. We can gender the term too. If you are a love interest (with the interest coming more from your end than mine), and I say “ain’t nobody got time for you” in an annoyed way, look you up and down, and roll my eyes, I am telling you that: a) I am not ever going to be interested in you; b) you are stupid, AND; c) your momma dresses you funny. Yes, all that from 6 words. If I say this about my boss, colleague, or some fool with a title or “authority,” I am calling them stupid and useless to my life, other than as another source of oppression, which I hardly need more of (which was EXACTLY what Sweet Brown was actually saying). Yup, all that from 6 words. This is precisely why translation exercises from Ebonics-to-Standard-English or simplistic contrastive analysis don’t work: the context of Black Language always suffers and loses depth of meaning, hardly a coincide since we live in a world where its speakers are not considered people who produce deep sweet brown meanings either.

It goes deeper still. Since the expression always uses the word time along with any variety of emphatic double negatives, we have to notice how time is configured completely outside of a western norm. The use of time in “I ain’t got time fa dat” does not reference the here-and-now alone. This means we need to turn to all that AfroCentric stuff that white academics and their bourgeois allies of color think is so, so far beneath their high-brow western theories of their western selves. This expression is based on an Africanized notion of time! Time here counters the run-til-you-are-ragged hustle under hyper-consumption and neoliberalism. And yet, the expression also makes time cyclical, non-linear, and, therefore, more of the spirit than of the temporal body (maybe even something like habitual be). Given its Africanized originary impulse, its place as a marker of oppression, and its circulation in the context of white institutions, it is a markedly black expression, not simply because black people have produced it but because THEIR EXPERIENCE has produced it.

It didn’t surprise me that folk couldn’t see depth into what Sweet Brown was saying and opted for black-face performances instead. Academics/scholars who imagine themselves to study language or rhetoric don’t do much better either. They too, and proudly so, take a white framework and simply apply that to black lives and act as if they have created anything other than the same kind of blackface caricature of the likes of those offensive memes about Sweet Brown. I am not suggesting that black scholars not use white theorists, since that would be stupid. But I have also never forgotten Professor Sylvia Wynter’s warning either: that when you borrow and inform yourself, you must ALWAYS notice when race as an overarching sociogenic code of our present episteme is untheorizable/unseeable in a scholar’s work. I like to use Black Rhetoric to understand those kinds of academic slippages and the slippin’ and slidin’ that academics do in the context of whiteness: I ain’t got no time for that.

“Christmas always came to our house, but Santy Claus only showed up once in a while.” I love this line. It does so much in just 16 words. “Santy Claus” is marked as Other both in how it is named and located as a secondary, um, clause. It literally delivers Christmas from its consumerist saga and resets it within new sets of practices and values. The line comes from none other than the children’s book written by

“Christmas always came to our house, but Santy Claus only showed up once in a while.” I love this line. It does so much in just 16 words. “Santy Claus” is marked as Other both in how it is named and located as a secondary, um, clause. It literally delivers Christmas from its consumerist saga and resets it within new sets of practices and values. The line comes from none other than the children’s book written by  In the story, beautifully illustrated by Jerry Pinkney, three sisters receive one special gift: Baby Betty Doll. The sisters, once inseparable— called chickadees by their mother, because they were always chattering, twittering, and doing everything together— are now fighting amongst one another. When Santy Claus actually does visit in one auspicious year with the beloved Baby Betty Doll, conflict arises since all three must share the one, coveted doll. Nella convinces her two sisters that Baby Betty was her idea and written request to Santy so she should receive the doll. The other two sisters begrudgingly agree and go on to play outside without their sister. Nella thinks she is going to have the best day of her life, only to find out it becomes the worst: playing with the doll, all alone, without her sister’s company, bores her to tears. She apologizes to her two sisters and from there, they work out a plan so that the doll can belong to all three of them. It the end, they learn that all they really want for Christmas is themselves, their creativity, togetherness, and family, not a store-bought item.

In the story, beautifully illustrated by Jerry Pinkney, three sisters receive one special gift: Baby Betty Doll. The sisters, once inseparable— called chickadees by their mother, because they were always chattering, twittering, and doing everything together— are now fighting amongst one another. When Santy Claus actually does visit in one auspicious year with the beloved Baby Betty Doll, conflict arises since all three must share the one, coveted doll. Nella convinces her two sisters that Baby Betty was her idea and written request to Santy so she should receive the doll. The other two sisters begrudgingly agree and go on to play outside without their sister. Nella thinks she is going to have the best day of her life, only to find out it becomes the worst: playing with the doll, all alone, without her sister’s company, bores her to tears. She apologizes to her two sisters and from there, they work out a plan so that the doll can belong to all three of them. It the end, they learn that all they really want for Christmas is themselves, their creativity, togetherness, and family, not a store-bought item. Like she does with Christmas in the Big House, Christmas in the Quarters, McKissack uses historical research to write The All-I’ll-Ever-Want Christmas Doll also. This book is not a world of make believe or simply a story about learning to share. I was surprised to see how many introductions and discussions of the book leave out the one, very important character who McKissack introduces at the very start in her “Note about the Story”: Mary Lee Bendolph. Once again, we see the white liberalist imperative of a false “universalism” wipe away black historical specificity. The All-I’ll-Ever-Want Christmas Doll is the narrative of

Like she does with Christmas in the Big House, Christmas in the Quarters, McKissack uses historical research to write The All-I’ll-Ever-Want Christmas Doll also. This book is not a world of make believe or simply a story about learning to share. I was surprised to see how many introductions and discussions of the book leave out the one, very important character who McKissack introduces at the very start in her “Note about the Story”: Mary Lee Bendolph. Once again, we see the white liberalist imperative of a false “universalism” wipe away black historical specificity. The All-I’ll-Ever-Want Christmas Doll is the narrative of  It was a fellow second grader who first told me that Santa Claus was not real. I remember coming home with many questions, not about Santa, but about everything else I could think of. The tooth fairy, the Easter Bunny, Mickey Mouse, the talking animals in my children’s books, Scooby Doo, Bugs Bunny and EVEN Wonder Woman were not real. That’s a lot for a child to ingest in one day. There was one fiction that I never questioned though. It was a story that a family friend, who I think of as an uncle, told me. I had come home excited from school talking non-stop about what I had learned about President George Washington. My uncle told me to rethink my excitement because the Big G.W. wasn’t all that. According to him, GW chopped down momma’s cherry tree, lied about it, and so my uncle had no choice but to whup dat ass. I told everyone about my amazing uncle after that, despite the naysayers and player-haters who insisted that my uncle was not old enough to know GW. My uncle IS old was my vehement response. Plus, my uncle had animatedly replayed the whole conversation for me. You couldn’t make up something like that as far as I was concerned. I offer this story not to highlight my eventual discovery of my uncle’s age and tall-tale-telling but as a way to counter a problematic Christmas book about African American children. The fact that my uncle, a man who cannot read and write, replaced white greatness with people who look like me in an everyday children’s conversation is a kind of love and political capacity that escapes far too many.

It was a fellow second grader who first told me that Santa Claus was not real. I remember coming home with many questions, not about Santa, but about everything else I could think of. The tooth fairy, the Easter Bunny, Mickey Mouse, the talking animals in my children’s books, Scooby Doo, Bugs Bunny and EVEN Wonder Woman were not real. That’s a lot for a child to ingest in one day. There was one fiction that I never questioned though. It was a story that a family friend, who I think of as an uncle, told me. I had come home excited from school talking non-stop about what I had learned about President George Washington. My uncle told me to rethink my excitement because the Big G.W. wasn’t all that. According to him, GW chopped down momma’s cherry tree, lied about it, and so my uncle had no choice but to whup dat ass. I told everyone about my amazing uncle after that, despite the naysayers and player-haters who insisted that my uncle was not old enough to know GW. My uncle IS old was my vehement response. Plus, my uncle had animatedly replayed the whole conversation for me. You couldn’t make up something like that as far as I was concerned. I offer this story not to highlight my eventual discovery of my uncle’s age and tall-tale-telling but as a way to counter a problematic Christmas book about African American children. The fact that my uncle, a man who cannot read and write, replaced white greatness with people who look like me in an everyday children’s conversation is a kind of love and political capacity that escapes far too many. On Cyber Monday, I searched the corners of google and bing for

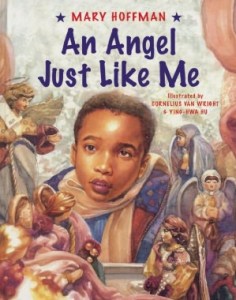

On Cyber Monday, I searched the corners of google and bing for  A friend recently suggested that I watch an interview with Marianne Williamson where she talks about love. Now, some of that New Age spirituality gets a little weird to me, but, hey, to each their own. Some of it just borrows too heavily from Non-Western spiritual traditions and remixes all of that for American, bourgeois individualism. Nevertheless, there are times when a definition or phrase moves me deeply. In this interview, Williamson gives a definition of love that describes black folk beautifully. She is not, of course, talking explicitly about black people, but about a kind of everyday practice that I attribute to them: “a spiritual, mental, emotional, personal strength that I develop in myself to refuse to see you as other people might have chosen to see you today.” She calls this a kind of sacred, daily practice when you “give birth, rebirth, to [someone’s] own self-confidence, their own belief in themselves, their own strength and glory, because you see what others might not see.” I get this kind of sacred practice and strength everytime I talk to one of my sistafriends and mentors who refuse to see me from the lens of a violating, white, dominant gaze. I also get this every time I talk to one of my colleagues of color about something that has happened; they don’t ever act like I am overreacting or sweep everything under the rug like most white colleagues do— they have the ability to see and hear me and offer an alternative paradigm outside of white norms. I can’t think of a better definition than SACRED to describe the teachers, mentors, parents, family, extended family, scholars, friends who see the beauty of black children and families, and choose to portray that back, despite the world that constantly suggests otherwise. I can tell you that it is ONE HELLUVA thing to step out in a world each day that tries to minimize my expertise, question my awareness/consciousness/ability… but then come home to a partner, sistafriend, auntie, uncle, pops, momma, or neighbor who tells me to keep on keeping on, moves me past the toxic energy of dumb folk, and reminds me of who and what I am. One Helluva Thing! Though this book ain’t worth the paper it is printed on, its ignorance did remind me to always remember what Black Love is and does.

A friend recently suggested that I watch an interview with Marianne Williamson where she talks about love. Now, some of that New Age spirituality gets a little weird to me, but, hey, to each their own. Some of it just borrows too heavily from Non-Western spiritual traditions and remixes all of that for American, bourgeois individualism. Nevertheless, there are times when a definition or phrase moves me deeply. In this interview, Williamson gives a definition of love that describes black folk beautifully. She is not, of course, talking explicitly about black people, but about a kind of everyday practice that I attribute to them: “a spiritual, mental, emotional, personal strength that I develop in myself to refuse to see you as other people might have chosen to see you today.” She calls this a kind of sacred, daily practice when you “give birth, rebirth, to [someone’s] own self-confidence, their own belief in themselves, their own strength and glory, because you see what others might not see.” I get this kind of sacred practice and strength everytime I talk to one of my sistafriends and mentors who refuse to see me from the lens of a violating, white, dominant gaze. I also get this every time I talk to one of my colleagues of color about something that has happened; they don’t ever act like I am overreacting or sweep everything under the rug like most white colleagues do— they have the ability to see and hear me and offer an alternative paradigm outside of white norms. I can’t think of a better definition than SACRED to describe the teachers, mentors, parents, family, extended family, scholars, friends who see the beauty of black children and families, and choose to portray that back, despite the world that constantly suggests otherwise. I can tell you that it is ONE HELLUVA thing to step out in a world each day that tries to minimize my expertise, question my awareness/consciousness/ability… but then come home to a partner, sistafriend, auntie, uncle, pops, momma, or neighbor who tells me to keep on keeping on, moves me past the toxic energy of dumb folk, and reminds me of who and what I am. One Helluva Thing! Though this book ain’t worth the paper it is printed on, its ignorance did remind me to always remember what Black Love is and does. I was in a workshop with teachers when I found out Nelson Mandela died. Someone got a phone alert, of course, the best use of a handheld device that I have experienced all semester. The tributes online and on radio have been simply touching. On the radio stations that I frequent, it seems deejays everywhere are interrupting themselves to honor and remember Mandela with a relevant song or memory. It seems fitting— Nelson Mandela interrupted the trek of white supremacy. Interrupting our lives— from the regular sounds that surround us or our everyday discourses— seems like the most honorable tribute we could make.

I was in a workshop with teachers when I found out Nelson Mandela died. Someone got a phone alert, of course, the best use of a handheld device that I have experienced all semester. The tributes online and on radio have been simply touching. On the radio stations that I frequent, it seems deejays everywhere are interrupting themselves to honor and remember Mandela with a relevant song or memory. It seems fitting— Nelson Mandela interrupted the trek of white supremacy. Interrupting our lives— from the regular sounds that surround us or our everyday discourses— seems like the most honorable tribute we could make.