It was a fellow second grader who first told me that Santa Claus was not real. I remember coming home with many questions, not about Santa, but about everything else I could think of. The tooth fairy, the Easter Bunny, Mickey Mouse, the talking animals in my children’s books, Scooby Doo, Bugs Bunny and EVEN Wonder Woman were not real. That’s a lot for a child to ingest in one day. There was one fiction that I never questioned though. It was a story that a family friend, who I think of as an uncle, told me. I had come home excited from school talking non-stop about what I had learned about President George Washington. My uncle told me to rethink my excitement because the Big G.W. wasn’t all that. According to him, GW chopped down momma’s cherry tree, lied about it, and so my uncle had no choice but to whup dat ass. I told everyone about my amazing uncle after that, despite the naysayers and player-haters who insisted that my uncle was not old enough to know GW. My uncle IS old was my vehement response. Plus, my uncle had animatedly replayed the whole conversation for me. You couldn’t make up something like that as far as I was concerned. I offer this story not to highlight my eventual discovery of my uncle’s age and tall-tale-telling but as a way to counter a problematic Christmas book about African American children. The fact that my uncle, a man who cannot read and write, replaced white greatness with people who look like me in an everyday children’s conversation is a kind of love and political capacity that escapes far too many.

It was a fellow second grader who first told me that Santa Claus was not real. I remember coming home with many questions, not about Santa, but about everything else I could think of. The tooth fairy, the Easter Bunny, Mickey Mouse, the talking animals in my children’s books, Scooby Doo, Bugs Bunny and EVEN Wonder Woman were not real. That’s a lot for a child to ingest in one day. There was one fiction that I never questioned though. It was a story that a family friend, who I think of as an uncle, told me. I had come home excited from school talking non-stop about what I had learned about President George Washington. My uncle told me to rethink my excitement because the Big G.W. wasn’t all that. According to him, GW chopped down momma’s cherry tree, lied about it, and so my uncle had no choice but to whup dat ass. I told everyone about my amazing uncle after that, despite the naysayers and player-haters who insisted that my uncle was not old enough to know GW. My uncle IS old was my vehement response. Plus, my uncle had animatedly replayed the whole conversation for me. You couldn’t make up something like that as far as I was concerned. I offer this story not to highlight my eventual discovery of my uncle’s age and tall-tale-telling but as a way to counter a problematic Christmas book about African American children. The fact that my uncle, a man who cannot read and write, replaced white greatness with people who look like me in an everyday children’s conversation is a kind of love and political capacity that escapes far too many.

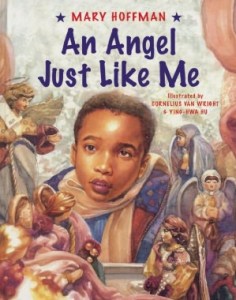

On Cyber Monday, I searched the corners of google and bing for multicultural Christmas books for children. I wanted to especially see what African American children in such books did and how the idea of Christmas was depicted in black homes (I decided to save Kwanzaa for later which produces much more interesting books, quite obviously). I purchased the 1997 text, An Angel Like Me by Mary Hoffman, because the illustrations by Cornelius Van Wright and Ying-Hwa Hu are just stunning. I was drawn to the text because it takes on the issue of why Christmas paraphernalia features white characters and not brown ones. Everything that I read online seemed to offer a great review. While I don’t agree with arguments that white writers can’t compose stories for black children, in this case, those arguments gain some validity. The lack of connection to black families, black storytelling, and race pride distorts this writer’s entire ability to compose a narrative about black children and their families.

On Cyber Monday, I searched the corners of google and bing for multicultural Christmas books for children. I wanted to especially see what African American children in such books did and how the idea of Christmas was depicted in black homes (I decided to save Kwanzaa for later which produces much more interesting books, quite obviously). I purchased the 1997 text, An Angel Like Me by Mary Hoffman, because the illustrations by Cornelius Van Wright and Ying-Hwa Hu are just stunning. I was drawn to the text because it takes on the issue of why Christmas paraphernalia features white characters and not brown ones. Everything that I read online seemed to offer a great review. While I don’t agree with arguments that white writers can’t compose stories for black children, in this case, those arguments gain some validity. The lack of connection to black families, black storytelling, and race pride distorts this writer’s entire ability to compose a narrative about black children and their families.

The story gets set off when a black family breaks one of its angel ornaments. Tyler, the young protagonist of the book, immediately asks why angels are always white, blonde, and feminine. No one can answer his question. NO. BODY. He even asks his mother why Jesus is depicted as white. Again, no one has an answer for him. Not a single adult can answer and most seem to say: hmmm, I never noticed that. Really? No single black adult in the book has ever thought about whiteness? How on earth have these black folk survived slavery, Post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow, Reagonomics, post-racism? Finally, at the end of the book, an art student who babysits for the family, who also couldn’t answer Tyler’s question about the prevalence of white angels, carves Tyler a brown angel that looks just like him and the story ends happily ever after. Now, for some folk, this story is not enough cause for disgust. Well, they are wrong. Get off this blog! It ain’t for you or about you. Only someone who does not know black families and cannot sociologically imagine how they function in this world could write this kind of book. Could you ever imagine me going up to my uncle, asking him about whiteness, and him NOT having any answer? Do you really think that any child in my family who asks why Jesus, Santa, or angels are depicted as white finds people who are so stumped that they cannot provide any answer? You think I ain’t got some answers that I relate in fantastically creative narratives? Do you think that all we do is sit around and eat sweet potato pie over the holidays and never talk about anything? What a stoopit book!

A friend recently suggested that I watch an interview with Marianne Williamson where she talks about love. Now, some of that New Age spirituality gets a little weird to me, but, hey, to each their own. Some of it just borrows too heavily from Non-Western spiritual traditions and remixes all of that for American, bourgeois individualism. Nevertheless, there are times when a definition or phrase moves me deeply. In this interview, Williamson gives a definition of love that describes black folk beautifully. She is not, of course, talking explicitly about black people, but about a kind of everyday practice that I attribute to them: “a spiritual, mental, emotional, personal strength that I develop in myself to refuse to see you as other people might have chosen to see you today.” She calls this a kind of sacred, daily practice when you “give birth, rebirth, to [someone’s] own self-confidence, their own belief in themselves, their own strength and glory, because you see what others might not see.” I get this kind of sacred practice and strength everytime I talk to one of my sistafriends and mentors who refuse to see me from the lens of a violating, white, dominant gaze. I also get this every time I talk to one of my colleagues of color about something that has happened; they don’t ever act like I am overreacting or sweep everything under the rug like most white colleagues do— they have the ability to see and hear me and offer an alternative paradigm outside of white norms. I can’t think of a better definition than SACRED to describe the teachers, mentors, parents, family, extended family, scholars, friends who see the beauty of black children and families, and choose to portray that back, despite the world that constantly suggests otherwise. I can tell you that it is ONE HELLUVA thing to step out in a world each day that tries to minimize my expertise, question my awareness/consciousness/ability… but then come home to a partner, sistafriend, auntie, uncle, pops, momma, or neighbor who tells me to keep on keeping on, moves me past the toxic energy of dumb folk, and reminds me of who and what I am. One Helluva Thing! Though this book ain’t worth the paper it is printed on, its ignorance did remind me to always remember what Black Love is and does.

A friend recently suggested that I watch an interview with Marianne Williamson where she talks about love. Now, some of that New Age spirituality gets a little weird to me, but, hey, to each their own. Some of it just borrows too heavily from Non-Western spiritual traditions and remixes all of that for American, bourgeois individualism. Nevertheless, there are times when a definition or phrase moves me deeply. In this interview, Williamson gives a definition of love that describes black folk beautifully. She is not, of course, talking explicitly about black people, but about a kind of everyday practice that I attribute to them: “a spiritual, mental, emotional, personal strength that I develop in myself to refuse to see you as other people might have chosen to see you today.” She calls this a kind of sacred, daily practice when you “give birth, rebirth, to [someone’s] own self-confidence, their own belief in themselves, their own strength and glory, because you see what others might not see.” I get this kind of sacred practice and strength everytime I talk to one of my sistafriends and mentors who refuse to see me from the lens of a violating, white, dominant gaze. I also get this every time I talk to one of my colleagues of color about something that has happened; they don’t ever act like I am overreacting or sweep everything under the rug like most white colleagues do— they have the ability to see and hear me and offer an alternative paradigm outside of white norms. I can’t think of a better definition than SACRED to describe the teachers, mentors, parents, family, extended family, scholars, friends who see the beauty of black children and families, and choose to portray that back, despite the world that constantly suggests otherwise. I can tell you that it is ONE HELLUVA thing to step out in a world each day that tries to minimize my expertise, question my awareness/consciousness/ability… but then come home to a partner, sistafriend, auntie, uncle, pops, momma, or neighbor who tells me to keep on keeping on, moves me past the toxic energy of dumb folk, and reminds me of who and what I am. One Helluva Thing! Though this book ain’t worth the paper it is printed on, its ignorance did remind me to always remember what Black Love is and does.

This little children’s book simply doesn’t pass mustard for representing black children and families. You need to see us before you can write about us. There are authors who represent exactly the kind of love I have described and who do achieve a rewriting for black children. I will turn my attention to them now.